A shift in surgical procedures towards minimally invasive techniques has greatly complicated surgical education with a major potential impact on emergency patient care.

Introduction

This summer a former resident of mine – now an older surgeon himself – asked me whether I’d be interested in re-activating my surgical career (not a simple thing to do). As explanation, he mentioned a critical shortage of experienced surgeons in traditional surgical techniques, as present day’s education is now mainly focused on minimally invasive procedures. During the past ten years this has become a major issue, particularly in trauma and emergency surgery, where often “open” procedures are necessary.

Apparently, such basic skills are now mainly available amongst older and soon-to-retire surgeons, whose rapid attrition particularly affects staffing in smaller hospitals. Thus, patients requiring such operations may need to be transported to a major medical facility for a procedure that in the past could have been managed locally, adding to their morbidity and mortality risks because of transportation issues and other delays in treatment.

Only a few weeks later, while in Europe, a chance meeting with a retired vascular surgeon and former president of a national surgical society confirmed a similar situation on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean: a severe shortage of adequately trained young surgeons, understaffing of local hospitals and overburdened referral centers:

Back in the US I have tried to research the subject of recent surgical education and changing levels of competence. Here are some of the results of this review:

The Facts

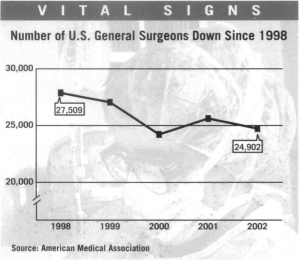

A recent assessment of the general surgery (GS) workforce in the US showed there has been a steady decline of GS surgeons vs. a fast growing US population[ii]:

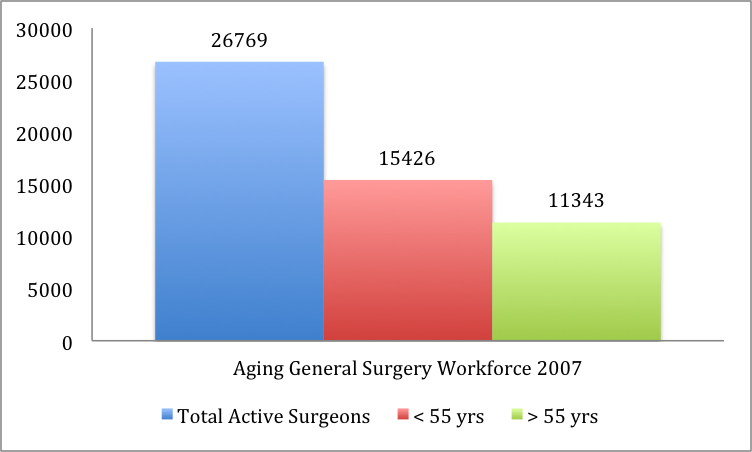

In 2008 more than 40% today’s general surgeons were 55 years or older:

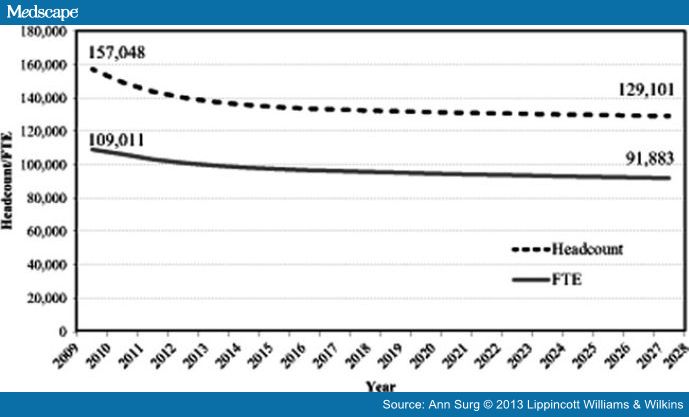

Forecasts show also that overall surgeon supply will decrease 18% during the period from 2009 to 2028 with declines in all specialties except colorectal, pediatric, neurological surgery, and vascular surgery. The most rapid decrease occurs in the first 5 years as the number of retiring surgeons substantially exceeds new entrants. Headcount declines more rapidly than fulltime equivalents over the forecast period because, although an increasing number of women are projected to enter the workforce who will provide fewer clinical hours, on average, younger surgeons of both sexes work more hours in patient care than surgeons who are nearing retirement age. The simulations also suggest that none of the proposed changes to increase graduate medical education currently under consideration will be sufficient to offset declines:

(Legend: Headcount: Surgeons in Practice. FTE: Full Time Equivalent)

CONCLUSIONS: The length of time it takes to train surgeons, the anticipated decrease in hours worked by surgeons in younger generations, and the potential decreases in graduate medical education funding suggest that there may be an insufficient surgeon workforce to meet population needs. Existing maldistribution patterns are likely to be exacerbated, leading to delayed or lost access to time-sensitive surgical procedures, particularly in rural areas.[iii]

Dr. Erik Hasenboehler MD, now an Orthopedic surgeon at John Hopkins University, presented a model for Acute Care Surgery education because of concerns related to lifestyle issues and maintenance of adequate operative experience, as well as dealing with patients’ whose outcome may be unsatisfactory:

- More and more surgeons are narrowing their practice

- More general surgery residents pursue subspecialty training

- Surgical specialists may no longer feel qualified or confident to perform general surgical procedures needed in the ED

- Specialists may refuse to take emergency call

- Specialists may take much longer to perform surgical procedures that they no longer routinely perform.[iv]

A number of factors have contributed to this:

A change in surgical education:

- “OR time is too valuable to permit acquisition of basic technical skills. Simulators, inanimate skills training stations, and animate models” [v], have replaced learning surgical technique by assisting on lots of cases.

- Shift work—the current method of meeting (a surgical resident’s) duty hour quotas—risks chopping clinical experience into short, incoherent pieces. In a setting with inconsistent continuity of care, the sum of the experiential parts of surgical training is less than the whole.

- The 80-hour workweek has effectively taken 6 months to 1 year of in-hospital time out of residency.

- 50% of the graduates had not performed even half of 121 “essential operations” (2005 data).

- Only 6 – 14% of the resident’s total working time during a five-year training program is spent in the Operating Room learning those essential operations.

- 30% of (graduates accepted into fellowship programs) were not prepared for operative cases and nearly two thirds could not work unsupervised for a significant period of time (Based on a survey of program directors):

- Young trainees are no longer interested in the lifestyle demands of a traditional surgical practice.

A shift away from general surgery practice:

- Historically, surgical training programs have focused on training residents to pursue a variety of career paths, and most graduates entered GS practice without additional subspecialty training.

- Fellowship/subspecialty training increased from 30% to more than 80%, in part from a feeling of inadequacy to pursue a more broad-based practice.

- Burnout is common among American surgeons (35%) and is the single greatest predictor of surgeons’ satisfaction with career and specialty choice.[vii]

- General surgeons have decreased as a proportion of the total U.S. surgical workforce.

- 35% of general surgeons are >55 years old[viii] and capable of “open” procedures. In contrast, many younger surgeons are not, and will replace only a portion of their older colleagues when they retire.

The result:

- Fewer general surgeons will be available to treat an increasing demand for their services.

- Surgical graduates are unable to perform a broad range of open and laparoscopic operations competently, as a consequence of inadequate exposure during their residency training.

- Trauma and emergency surgery often requires the knowledge and ability to perform an “open” procedure, a skill that will be less and less available.

- In 2006, 30% (925) of the 3,107 US counties lacked a single surgeon and nearly 9.5 million Americans lived in those counties[ix].

How does that compare with, for instance, my general surgical training (from 1972 -1979, including various fellowships), and before starting a cardio thoracic and vascular surgery residency?

When I finished my training I had been exposed to and performed a wide variety of operations that included most major vascular, esophageal, lung, liver, pancreatic and other GI procedures, while as Chief Resident I managed a service that included 6-8 junior residents and medical students with an average of 50-60 in-house patients, for whom we were expected to provide total care.

True, my only exposure to endoscopic procedures during that period included bronchoscopies in untold numbers (at one point I had a chief resident who believed in “therapeutic bronchoscopies” for atelectasis and I used to make daily “bronchoscopy rounds”), and colonoscopy (way too dull in my mind in comparison to an esophagectomy, hepatectomy, lobectomy or AAA repair).

Attending surgeons provided a loosely structured supervision; while some were masters of their craft and attracted patient from far outside the region, others would not have been able to manage patients on their own – the reverse of what seems to be the case in more modern times!

There were enough cases to go around in my hospital, so that on any given day just about every resident would spend considerable time in the OR, and if deemed capable, perform the operation supervised by an attending.

It was understood that an absolute prerequisite for “doing the operation” included intimate knowledge of the case, surgical technique and the specific operation to be performed, as well as of all the patients the attending surgeon and resident had in common. Another major difference with more modern times: working hours: no upper limits and sleep was incidental to the workload.

I remember this period of my life with great fondness, including and especially the learning/teaching experiences my program offered. Ready for my CT residency? Absolutely! Ready for practice – at least the medical part? Bet ye!

However, I wish I’d learned a lot more about practice management and the realities of competition that thus far had only included competing for excellence.

Conclusions

A variety of explanations for what certainly appears a looming crisis in healthcare (if not already there) are available:

- A surgical residency education that continues to be limited to five years, with workweeks curtailed to 80 hours, but with a lot more to learn and a lot less time to do so.

- Lack of time in the OR: there is no replacement for practical experience!

- Excessive administrative duties: today’s physicians often spend 70% of their time on administration rather than on patient care.

- An excessive focus on endoscopic skills that probably should be acquired after basic training has been completed.

- The increased focus in a surgeon’s education on new endoscopic procedures is at the expense of learning how to operate conventionally.

- Surgical residents are not responsible for the quality of their training programs, only for the quality of their own work.

- I find it difficult to accept that program directors have failed to anticipate and adjust to the changing challenges of their protégées education.

- Surgeons compete in a shrinking marketplace with non-surgeons, who frequently perform similar operations and often control referral patterns.

- Even with an adjustment of residency training – if and when that will happen- it will take years to correct the present manpower shortage.

- Major surgical centers will be overburdened, as smaller hospitals no longer have the manpower to provide surgical services.

- It does explain those conversations with my two colleagues that have prompted this review.

Joan F. Tryzelaar, MD, FACS, FACCP

Addendum:

Since writing a draft for this article earlier this fall, another physician concluded in a NY Times article that the lack of young surgeons skills was mainly due to curtailing work hours without extending the training period required to gain necessary skills and experience, quoting:

“When you take a whole year’s worth of in-hospital experiences out of training, you can’t be surprised that the ‘product’ is not the same,” said Dr. Frank R. Lewis, executive director of the American Board of Surgery, the major credentialing body in surgery that administers the certifying exams.[x]

A telling comment to this article from a senior surgical resident (PGY6 means a sixth year resident) to the article read:

“As a PGY6, I am doing not that much more in cases than I did as a PGY3. I have stood on the attending side of the patient for cholecystectomies and appendectomies, and one colectomy. When I am an attending I will be expected to suddenly flip to the other side and take residents through cases that I have never done on my own. Doesn’t this frighten you?”[xi]

What frightens me most is that after 6 years of training this resident has yet to learn how to perform an appendectomy or cholecystectomy. How can anybody expect such a person to be capable of performing a safe procedure with that background!

JT

For those interested, below follows a review of the few articles that address the issue of rapidly changing surgical competence. One of the article titles is particularly striking: “General Surgery Residency Inadequately Prepares Trainees for Fellowship” (and thus for independent performance).

Review of literature

I. “Surgical Competence Today”:

- For the 121 operations program directors deem “essential” for a graduating resident to be able to perform competently and independently, the following facts from 2005 were documented:

- Graduating residents performed only 18 of the 121 operations more than ten times during residency. Graduating residents performed 83 of the 121 operations less than five times during training.

- 50% of the graduating residents in 2005 had not performed even one of 50 of the 121 essential operations.

- There is a wide variation in the five-year total number of cases (individual operative experience) among graduating chief residents (2785 vs. 600).

- In a presidential address entitled, “Why Jonny Cannot Operate,” Dr. Richard H. Bell stated that chief residents in surgery spend between 1148 and 2753 hours performing what he called essential 121 and other operations. This is only 6 to 14% of the resident’s total working time during a five-year training program.

- By comparison, it has been determined that approximately 10,000 hours or ten years of deliberate practice are required to become a chess master, elite athlete, or professional musician. Clearly, surgical residents are not exposed to an adequate number of cases nor do they practice enough to achieve minimum competence in a wide range of surgical procedures.

- How we train surgeons remains part of the problem. In 2007, a survey revealed that there is a wide disconnect between what teaching surgeons felt residents needed to do to prepare for a case and what the residents felt was proper preparation. While the attending surgeon thought the resident ought to read up on the natural history and pathophysiology of the disease under scrutiny, the resident was more interested in reviewing the technical aspects of the case. A national surgical education curriculum is being formulated and the methods for measuring competence are improving. Still, the system remains weighted with inertia. All of which leaves one to react with little surprise to the fact that 13% of today’s general and vascular surgery patients develop complications and 2% die postoperatively.

Key Points:

-

The expansion of general surgery with the added technical and cognitive requirements of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in addition to the demands of traditional open operations has made a five-year residency obsolete.

-

Surgical graduates are unable to perform a broad range of open and laparoscopic operations competently as a consequence of inadequate exposure during their residency training.

-

Solutions to this dilemma will require not only the continued improvement in surgical education methodology already in progress but also a redefinition of the field of general surgery.[xii]

II. “Transition to [Surgical] Practice”:

…. A recent paper presented at the American Surgical Association reported on a survey of fellowship program directors, which noted that 30 percent of fellows were not prepared for operative cases and nearly two thirds could not work unsupervised for a significant period of time… The fact that 80 percent of general surgery graduates pursue fellowships likely stems, at least in part, from a feeling of inadequacy to pursue broad-based practice.[xiii]

III. “… Perceived competence in surgical training”

The choice of fellowship training for 80% of trainees partially reflects that 38% are not confident about their skills with 5 years of training in GS (general surgery), including 23% of graduating chief residents.[xiv]

IV. “General Surgery Residency Inadequately Prepares Trainees ”

A recent article examined surgical residents readiness for practice and assess existing gaps between the abilities of graduating chief residents and the requisites of specialty fellowships (80% of graduating surgical residents go on to specialty training). A survey of fellowship program directors (PD) showed that incoming fellows (i.e. just graduated chief residents) were unable to perform 30 minutes of a major procedure independently in the operating room, and 30% of PDs felt that new fellows could not independently and safely perform basic operations such as a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[xv]

V. Perhaps, the closest to an admission of young surgeons lack of competence comes from comments by F.R. Lewis, Jr (Philadelphia, PA) reviewing the above presentation:

… (During the past) 20 years the surgical environment has changed dramatically. Gastric surgery has markedly decreased; biliary tree surgery has virtually disappeared; abdominal vascular surgery for general surgical residents has also virtually disappeared; and trauma experience has decreased by two thirds. Several major categories of surgery no longer exist because of changes in the environment and improved drug treatment of diseases. That phenomenon is not reversible.

… One area that is under the control of program directors and chairs of surgery is that the exposure of surgical residents to the operating room in the early years of residency is remarkably poor. The average number of operations done by a first-year resident is presently fewer than 2 per week. The average number of operations done by a second-year resident is between 2 and 3 per week. These are residents who are spending 80 hours per week in the hospital but doing only 2 or 3 operations during this period, operations that arguably could be done in half a day.

It would be hard to imagine a less efficient educational process. If we do not expose residents to the operating room early and take advantage of the opportunities to give them more advanced training, their progression in later years is severely compromised. There is no reason that junior residents could not be doing much more operatively than they are currently.

… Residents have markedly decreased experience with open surgery because of the conversion of open surgery to laparoscopic surgery. The problem here is that the complex open operations that were previously done by general surgical residents have not been replaced by comparable laparoscopic operations of equal complexity. Fellowships in advanced laparoscopic surgery and the other GI areas are not available for residents.

… The decreased autonomy and independence of residents is undoubtedly a major factor, but one that is largely beyond our control, involving multiple ethical, legal, and other issues that are not easy to change.

Finally, there is the issue of work hours. The 80-hour workweek has effectively taken 6 months to 1 year of in-hospital time out of residency, hours that focused most heavily on evening and weekend experience, when there was more opportunity for independence and autonomy.[xvi]

[i] What makes a competent surgeon? Experts’ and trainees’ perceptions of the roles of a surgeon. Sonal Arora, et al. The American Journal of Surgery (2009) 198, 726–732.

[ii] A Longitudinal Analysis of the General Surgery Workforce in the United States, 1981-2005, Arch Surg. 2008;143(4):345-350. doi:10.1001/archsurg.143.4.345.

[iii] Projecting Surgeon Supply Using a Dynamic Model. Erin P Fraher, et all; Annals of surgery, 2013; 257(5):867872.

[iv] Acute Care Surgery: Quo Vadis? Erik Hasenboehler, Acute Care Surgery UK.

[v] National efforts to reform residency education in surgery. Sachdeva AK, et all; Acad Med. 2007; 82(12): 1200-1210.

[vi] General Surgery Residency Inadequately Prepares Trainees for Fellowship. Results of a Survey of Fellowship Program Directors. Rohan Jeyarajah et al; Annals of Surgery. 2013;258(3):440-449.

[vii] Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Shanafelt TD, et al; Ann Surg. 2009 Sep; 250(3): 463-71.

[viii] The Aging Surgeon Population, Elizabeth Walker et al; ACS Policy Research Institute, May, 2010.

[ix] Surgical Deserts in the US: Places Without Surgeons. Daniel Belsky et al; ACS Policy Research Institute, July 9, 2009.

[x] Are Today’s New Surgeons Unprepared? NYTimes, December 12, 2013.

[xi] Comment 11, Resident: Are Today’s New Surgeons Unprepared? NYTimes, December 12, 2013.

[xii] Surgical Competence Today. What Have We Gained? What Have We Lost?

David W. Page, MD, FACS South Med J. 010; 103(12): 12321234.

[xiii] ACS Transition to Practice program offers residents additional opportunities to hone skills. J. David Richardson, MD, FACS PUBLISHED American College of Surgeons, September 1, 2013.

[xiv] Early sub-specialization and perceived competence in surgical training: are residents ready? Coleman JJ et al; J Am Coll Surg. 2013 Apr;216(4):764-71.

[xv] General Surgery Residency Inadequately Prepares Trainees for Fellowship. Results of a Survey of Fellowship Program Directors. Rohan Jeyarajah et al; Annals of Surgery. 2013;258(3):440-449.

[xvi] Comments, General Surgery Residency Inadequately Prepares Trainees for Fellowship. Rohan Jeyarajah et al; Annals of Surgery. 2013;258(3):440449.

Comments 1

Thank you so much for being honest in your assessment of general surgical training today! I worked in Diagnostic Imaging/Mammography/Dexa scans/ lots of surgeries /CT and as an Hospital Imaging Clinical Instructor for 30 yrs. I completely understand your views! I have worked with many inadequate surgeons and MDs. But also great ones. I go to the VA for care now and my care has been good. Imaging was a post Navy Career. I am having health issues from a large HH and will more than likely need surgery! I would prefer to monitor my own surgery,awake, if I could! Lol. I ask lots of questions and do my research. But since I no longer work in the field and never worked at the VA, I can not critique a surgeon now!

I had to have a cervical 2 level fusion after an injury. I waited over 15 years for technology to catch up. (Posterior access being done at the time). I worked (Imaging) with my surgeon every week,1 to 2 days, for over a year before choosing him! He wanted a dedicated, competent Imaging Technologist and not whoever is on surgery rotation that day. Speaking out is the right thing to do! I appreciate it!